Argument: Zero tolerance policing is the correct approach to law and order in a modern democracy.

I had an argument years ago with a friend about policing. We were arguing about the then Irish Minister for Justice. I was of the opinion that he was slightly to the left of Mussolini (but only slightly), and that he was an advocate of ‘zero tolerance’ in policing. She responded by saying that he was right to have no tolerance for crime of any sort. I was flabbergasted and couldn’t speak. I was tongue-tied because I had so much to say and didn’t know where to begin.

Maybe she was right in the macro sense, that strong policing leads to less crime. It’s unlikely, but even with the data before us it’s hard to find an unequivocal answer. There are many socio-economic factors that lie behind crime statistics, as well as various cultural, moral, and historical factors that influence matters of crime and punishment. There are so many moving parts that no matter how much data are crunched there are always reasons to believe that any conclusions are merely correlated.

I would love to run an exhaustive study on the factors that contribute to the make-up of our societies, but there are so many other arguments weighing on my mind and demanding my attention. Needless to say, whatever conclusions I come to here are not definitive. They merely indicate possible areas of investigation for future arguments I’m bound to have.

The Global Organised Crime Index has produced a fantastic map of the disposition of organised crime around the world.

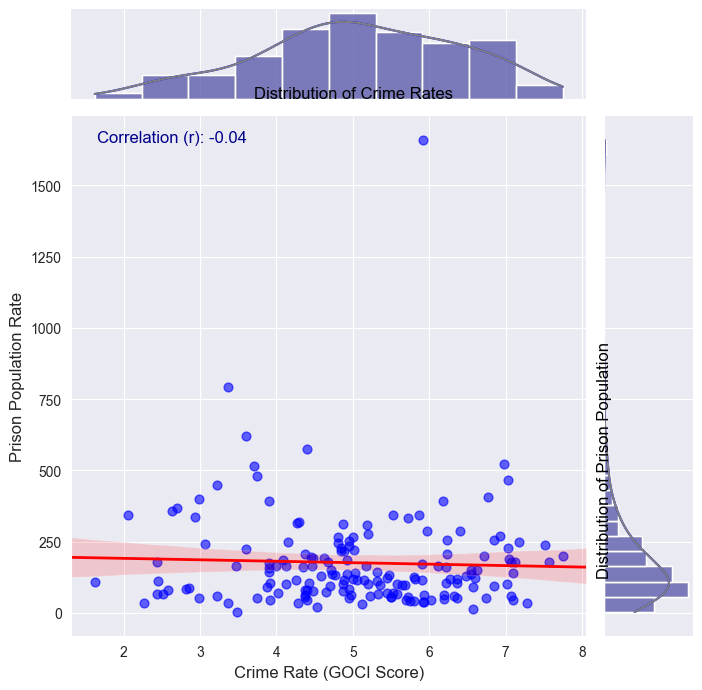

My simple idea was to compare the overall crime index of each country to their rates of imprisonment. The organised crime info is from 2023 and the prison data from 2024. I don’t consider this significant as, although prison figures are rising continually, the disparity between 2022 and 2024’s figures isn’t very large (I could have created a mean of 2022 and 2024 which would have solved the problem – next time).

ColIation of prison data from around the world was conducted by the World Prison Brief (consider a donation). I apologise for how difficult it might be to see the details on the graph, I considered just showing the head and tail but decided against it. I think it’s important to get an idea of the high variability of imprisonment worldwide. Accurate figures are difficult to acquire in many cases due to poor reporting, so this is a best approximation. For organised crime results refer to the ocindex above.

Here is what my quick analysis revealed. The scatterplot compares prison rates with the organised crime index. The histograms show the distributions of both sets. Important to note that crime rates show a normal distribution, but imprisonment is very left leaning showing how significant societal factors are in sentencing. The red line shows the linear regression (for what it’s worth), and the correlation between the two is shown in the top left of the main graph.

There are outliers (El Salvador especially), but I removed them when calculating the correlation coefficient. It appears there is little or no correlation between general crime figures and rates of imprisonment.

What to make of it all?

In further studies I’d like to compare recidivism rates against prison rates and overall crime. Criticising the justice of prison sentences and the length of terms handed out is one thing, but it’s as important to judge the ethos and purpose behind the institution – does it exist to punish the criminal or to rehabilitate them? That is outside the remit of this study, but is essential to a deeper understanding of crime and punishment around the world.

What seems clear is that no matter how punitive a legal system is it has little or no effect on how much crime is committed. We all want to live in a fairer and more humane society, so how people are treated in prison, how long they are interned, and how likely they are to recommit, are important questions affecting how safe we feel within our societies. But prisons and prison sentences are not deterrents to crime – irrespective of whether a legal system is especially harsh or not.

Have I won my argument? Not really, it’s too complicated a question to be satisfied with such a surface study. But I’ve shown that she certainly can’t claim success for zero tolerance. Humanist values and an understanding of the conditions that drive crime are central to our social project. It’s not helped by sweeping generalisations on either side.